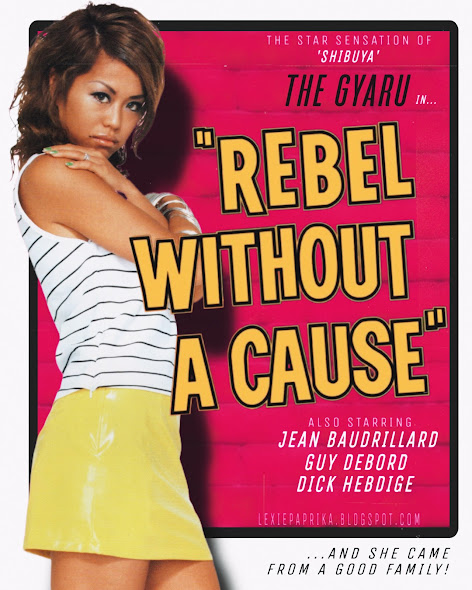

The Gyaru Illusion: A Rebellion Without a Cause?

Gyaru reached its peak at the turn of the 21st century. It was a bold cultural movement that offered young girls a means of self-expression beyond the narrow confines of Japan’s expectations of womanhood. Shibuya was their meeting ground. Sun-kissed and teetering on platform boots, they moved in packs, their limbs dusted in glitter and fruity-smelling lotions, their laughter cutting through the din of Center-Gai.

Gyaru was a rejection of a long-held beauty standard. But subversion (no matter how sincere) has a short shelf life. What was once shocking becomes marketable, and what was marketable becomes mainstream. Countercultural movements, once vilified and dismissed as fringe, eventually find their way onto runways and marketing campaigns.

The punk subculture, synonymous with a DIY ethos and sartorial anarchy, has been elevated by designers like Malcolm Mclaren and Vivienne Westwood, who incorporated bondage trousers, safety pins, studs, chains, and tartan into their collections. Similarly, grunge, once defined by thrift store finds and a disaffected, anti-corporate attitude, was famously reinterpreted by Marc Jacobs in his 1993 Perry Ellis collection, bringing ripped jeans and flannel to the world of luxury fashion.

In Japan, gyaru followed a similar trajectory. It was pioneered by high school girls who embraced radical self-expression, only for corporations to commodify their defiance and sell it right back to them through fashion magazines and mainstream branding, creating a self-perpetuating ouroboros of rebellion and consumption.

Gyaru is often described as a rebellion against traditional Japanese beauty norms. However, unlike a grassroots political movement, the gyaru’s protest was not an ideological one but aesthetic. Gyaru were not advocating for systemic change or engaging in overt political activism; rather, they were constructing identity through consumer choices. Their rejection of Japanese beauty norms was not framed through the lens of feminist discourse but was instead an aesthetic assertion of selfhood within a consumer-driven society.

This intersection of rebellion and consumerism made gyaru uniquely susceptible to commodification. Jean Baudrillard, in Simulacra and Simulation (1981), theorized that when media endlessly reproduces an image, it replaces reality itself, creating a self-contained system of meaning that no longer references an original. This happened to gyaru even at the height of its popularity: fashion magazines, clothing brands, and nightlife industries dictated the parameters of the subculture, ensuring that market forces had a hand in shaping its resistance. The question is not whether gyaru was "authentic" or "commercialized;” instead, it was always both. The more gyaru attempted to define itself through aesthetic resistance, the more it played into the logic of consumer spectacle, becoming a mediated construct that existed as much in advertising as it did in practice.

Gyaru became trapped in a loop of reinvention, forever cycling between rebellion and commodification.

Gyaru as a Rebellion Against Japanese Beauty Norms

From its inception, gyaru functioned as a rejection of Japan’s dominant feminine ideal: pale skin, natural beauty, and a reserved demeanor. Drawing inspiration from Californian beach culture, hostess aesthetics, and Japanese idols like Namie Amuro, gyarus cultivated an aesthetic that contrasted sharply with mainstream expectations of understated femininity. However, this emulation of Western beauty standards was not an attempt at authenticity but rather an exercise in hyperreality.

Baudrillard’s concept of the precession of simulacra posits that a representation can detach from its original referent and take on a life of its own. Gyaru did not simply borrow from Western fashion; it created a stylized, media-driven version of Western beauty that had no true reference point in reality. This manufactured aesthetic, endlessly reproduced in magazines and advertisements, became its own hyperreal construct. One that girls performed and embodied, often without any conscious reference to its supposed origins.

In this way, gyaru’s rejection of Japanese femininity was paradoxically a performance of another highly constructed femininity. The boldness, excess, and flamboyance of gyaru were not always natural expressions but mediated choices dictated by the ever-evolving standards of the subculture’s own imagery. This aligns with Baudrillard’s assertion that in a hyperreal society, authenticity is no longer a matter of referencing an original but rather maintaining the illusion of originality within a closed system of subcultural signs.

|

| from narita-akihabara.jp |

Media, Magazines, and Commodification

Fashion media played a crucial role in shaping the gyaru subculture. Publications like Egg, Popteen, and Ranzuki did not merely document gyaru fashion; they dictated its evolution. These magazines constructed gyaru as a self-referential aesthetic, feeding an endless cycle in which readers emulated the images they consumed, which in turn reinforced those images as authentic. Baudrillard describes this phenomenon as "the map preceding the territory," where the representation of culture becomes more real than the lived experience itself.

Additionally, Baudrillard’s The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures (1970) outlines how consumption operates as a system of signification, wherein cultural products serve not just functional purposes but communicate identity, status, and belonging. Gyaru exemplified this principle; fashion choices, tanning salons, colored contacts, and elaborate nails were not simply matters of personal style but signifiers of subcultural participation. Yet, this emphasis on visual markers of identity made gyaru highly susceptible to commercialization. Even the body itself became a curated, modifiable product, reinforcing the notion that selfhood could be purchased, produced, and perfected.

The role of consumerism in gyaru’s evolution cannot be overstated. While many subcultures formed around shared ideologies or musical preferences, gyaru was fundamentally rooted in aesthetic consumption. It was through the accumulation of specific cosmetic products, clothing brands, and accessories that one could fully embody the gyaru identity.

While gyaru, as a designation, can also describe an outspoken attitude or social behavior, it is near impossible to separate the attitude from the aestheticism and maintain recognizability. This further supports Baudrillard’s argument that modern consumer societies function through an endless cycle of signifiers, where meaning is derived not from substance but from participation in a system of appearances.

The Spectacle of Gyaru: When Image Becomes Reality

In The Society of the Spectacle (1967), Guy Debord argues that subcultures, once authentic expressions of resistance, are eventually transformed into commodified images that obscure their original meaning. This phenomenon was clearly visible in the evolution of gyaru. By the late 2000s, gyaru had become a spectacle, its representation in media eclipsing its lived reality. Fashion magazines amplified gyaru’s visibility, transforming it from a youth-driven subculture into a fully commercialized lifestyle brand.

The advent of social media in the 2000s accelerated this process, further detaching gyaru from its origins. As smartphones and platforms like Instagram and gyaru-focused blogs became ubiquitous in the late 2000s and early 2010s, gyaru culture was increasingly mediated through digital performances. The more gyaru was represented in these curated, visual-heavy spaces, the more its authenticity became defined by (and confined to) the act of being seen. By the 2010s, the subculture had reached a point where the spectacle of gyaru had overtaken its lived practice. It became a marketable image, a hyperreal fantasy that could be performed and consumed in fragments rather than lived as a cohesive experience.

Furthermore, the cyclical nature of gyaru’s popularity (its peak in the early 2000s, its decline in the mid-2010s, and its nostalgic revival in the Reiwa era) reinforces Debord’s assertion that the spectacle is self-perpetuating. Even as the original gyaru generation aged out of the subculture, its aesthetic continued circulating in media, repackaged for new consumers who engaged with gyaru as an image rather than an identity.

|

| from grinnell.edu |

Gyaru as Postfeminist Hyperreality: Empowerment or Performance?

The transformation scene is a well-worn trope. One that makeover shows, reality TV, and fashion media have milked dry since the early 2000s. A woman, dissatisfied with her appearance, undergoes a dramatic reinvention. The narrative is always the same: empowerment, but only through aesthetic transformation. Look better, live better… or so they say.

Gyaru, in many ways, was framed through this same logic. The subculture was often positioned as a rejection of traditional Japanese beauty norms, a rebellion against pale skin, dark hair, and soft-spoken femininity. But it wasn’t about dismantling those norms; it was about subverting them, amplifying hyper-feminine aesthetics until they became unrecognizable. Instead of natural beauty, gyaru chose extreme artifice: bleached hair, exaggerated eyes, deep tans, impossibly elaborate nails.

This ties directly into Baudrillard’s notion of hyperreality. In Simulacra and Simulation, he argues that in a world where simulations endlessly reproduce themselves, the distinction between the real and the artificial collapses. The simulation becomes the reality.

Gyaru embodied this perfectly: it wasn’t just a rejection of mainstream beauty. It was the creation of an entirely new, self-contained system of aesthetic meaning, one dictated by magazines, clothing stores, and nightlife industries. To be gyaru was to perform an identity that was both radical and carefully curated, rebellious and yet profoundly entrenched in consumerism.

The Paradox of Gyaru Empowerment

At its core, gyaru presented a challenge to Japan’s rigid expectations of femininity. It allowed young women to take control of their image, and to express themselves on their own terms. And yet, the subculture never truly escaped the trap of aesthetic labor. Gyaru may have rejected the natural, modest ideal but replaced it with a standard that (for some) was just as unattainable, just as expensive, time-consuming, and socially constructed. The hours spent tanning, the elaborate hairstyles, the endless cycle of subcultural fashion trends. Was this liberation, or was it another form of self-surveillance?

The paradox becomes even more pronounced when considering the overlap between gyaru and Japan’s hostess culture. Many gyaru worked in kyabakura (hostess clubs), where their exaggerated femininity was not just a personal choice but a marketable asset. In this context, gyaru’s rebellion was directly commodified for male consumption. It was a form of resistance, but one that operated within structures designed to sell beauty as a product.

Baudrillard’s concept of personalization as a consumer trap applies here. In The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures, he argues that consumer capitalism thrives on the illusion of individuality, that we are sold pre-defined versions of self-expression, packaged as personal choice. Gyaru weren’t following mainstream beauty norms, but they were still adhering to a carefully curated aesthetic, one reinforced by magazines, brands, and those in their community.

|

| Egg, 2021 |

Gyaru in the Reiwa Era: Nostalgia and the Hyperreal Resurrection

Subcultures never die. They just become TikTok aesthetics.

Gyaru, once a living community, has largely faded from Japan’s streets. The para-para clubbers, the sun-tanned legs peeking beneath the curtain of a purikura booth, the vibrant chaos of a culture that once thrived in physical spaces. All of it has been largely displaced, archived in fashion magazines, old Egg scans, and digital reuploads. Yet, gyaru’s image remains, repackaged as a Heisei-era fantasy, sold through Instagram reels and Shibuya 109 marketing campaigns.

It’s a tale as old as time: what was once radical becomes retro, and what was once subversive becomes quaint.

Baudrillard (1981) argued that Disneyland exists not merely as a form of entertainment but to convince us that America itself is real. It is a simulation that validates its own mythology. In the same way, modern gyaru nostalgia functions not as a revival of the subculture but as a reminder of a time that, in many ways, never truly existed. The gyaru revival isn’t about bringing back the movement in its rawest form; it’s about recreating a hyperreal fantasy of gyaru. One that has been softened, rebranded, and repackaged for mass consumption. The neon-lit chaos of Shibuya in the 2000s has been edited down into a clean, nostalgic mood board, an aesthetic to be scrolled past and filtered through social media algorithms.

The Shibuya 109 of today capitalizes on its nostalgic past. Retro-styled campaigns use the iconography of old-school gyaru: platform boots, slouchy socks, and early 2000s aesthetics. But the raw, rebellious energy is gone. The grit, the controversy, and the social opposition that once defined gyaru are more or less absent. In its place is curation and commercialization. Where gyaru once developed organically, shaped by high school girls testing the boundaries of fashion and femininity, today’s version is pre-packaged, flattened into an aesthetic that can be picked up and discarded at will.

This shift isn’t unique to gyaru. Subcultures, especially those rooted in fashion, are cyclical. Dick Hebdige (Subculture: The Meaning of Style, 1979) argued that subcultures begin as expressions of resistance, only to be sanitized, stripped for parts, and absorbed by the mainstream. But Baudrillard takes it a step further: in the age of hyperreality, the original event (the subculture as a living, breathing identity) becomes irrelevant. What matters is the representation, the curated aesthetic that lives on long after the movement itself has faded.

In this sense, gyaru now functions more as aesthetic currency than as an active subculture. In an era where nostalgia itself is an industry, gyaru is sold in fragments: a blurred, overly saturated edit set to an Ayumi Hamasaki song, an Instagram post of neatly arranged vintage Alba Rosa pieces, a limited-edition Shibuya 109 shopping bag that nods at the past without carrying any of its cultural weight. The hyperreal version of gyaru (one constructed through media images rather than lived experience) becomes more tangible than the real thing.

And yet, gyaru is not entirely dead. It continues to evolve in digital spaces, existing in a tension between revival and reinvention. But is this a true resurgence or simply another aesthetic trend detached from its original movement? The answer, like everything in hyperreality, is ambiguous. Gyaru today is not the subculture it once was, but it is also not entirely gone. It has become something else.

DIGITAL BEAUTIES by Julius Wiedemann

The Digital Gyaru and the Heisei Hyperreal Fantasy

For today’s gyaru revivalists, social media is the new Shibuya.

Where once the movement existed in physical spaces, gyaru now thrives in a curated, ephemeral digital landscape. TikTok and Instagram have replaced the old haunts in Shibuya and Ikebukuro, offering new platforms where gyaru can perform their aesthetic, not just for themselves but for an ever-scrolling audience. The streets of Tokyo are no longer the stage; social media is.

Yet this shift has made gyaru more hyperreal than ever.

At its peak, gyaru was at least something tangible. You could step onto Center-Gai and see it in action, feel its presence in the crush of bodies at 109, hear it in the chatter of gyaru-go, and witness its evolution in real-time as trends flared up and burned out within months. It was a lifestyle that required active participation, not just aesthetic adherence. But today, gyaru’s primary existence is mediated through the lens of social media, where filtered, edited, and algorithm-driven imagery dictates how the subculture is consumed and understood.

Baudrillard (1981) argues that hyperreality occurs when the distinction between the real and the representation collapses. When the simulation of a thing becomes more real than the thing itself, this is the paradox of the digital gyaru. The hyperreality of social media has flattened the subculture into a performance of itself, one that often exists independently from lived experience. The highly curated nature of Instagram feeds, the exaggerated edits of TikTok tutorials, and the nostalgia-drenched Y2K revival aesthetics all serve to reinforce a stylized version of gyaru rather than its organic and contradictory reality.

This is not to say that gyaru cannot exist authentically in digital spaces. Rather, the very nature of social media alters its framework. In previous decades, a girl became gyaru through participation. Through how she dressed, where she spent her time, and who she surrounded herself with. Now, one can become gyaru through self-documentation, through the accumulation of highly specific digital signifiers: a cleverly edited TikTok transition, a haul video of Liz Lisa dresses, a perfectly staged Instagram photo bathed in Heisei-era filters. This echoes Baudrillard’s concept of the precession of simulacra, where representation precedes and determines reality, where the performance of gyaru in media becomes more real than the lived subculture itself.

Gyaru is not dead, but it has transmuted. It has become something less real, yet more persistent. Unlike its predecessors, this version of gyaru does not require physical spaces to sustain itself. It does not need a Shibuya 109, a bustling crossing, or a shared community. It thrives in pixels and data, hashtags and explore pages.

Perhaps this is the inevitable fate of all subcultures in the digital age. Not death, but permanent circulation. A subculture does not need to be physically present to be experienced; it only needs to be seen. And in that sense, gyaru may be more alive than ever, even as it exists primarily as an image of itself.

A Rebellion Reframed

Roland Barthes’ Mythologies (1957) suggests that cultural movements, when stripped of their historical contexts, are transformed into myths, presented as natural, timeless phenomena rather than socially constructed practices. This has been the fate of gyaru: its history of social defiance, rejection from mainstream society, and eventual commodification have been largely diluted in favor of a media-friendly fantasy of carefree youth culture.

Yet, this does not mean that modern gyaru are merely engaging in performance. Both things can be true at once: one can participate in gyaru sincerely while also being complicit in its commodification. Even at its height, gyaru was both rebellion and spectacle, self-expression and consumerism. To be gyaru today means navigating this paradox, to embody the aesthetic while also recognizing that it exists within a hyperreal framework.

Perhaps authenticity and performance are no longer opposites but interwoven realities, especially in an era where identity is curated, aestheticized, and mediated through screens.

Maybe the question isn’t whether gyaru was real but whether, in a postmodern age of endless reinvention, realness matters much at all.

No comments:

Post a Comment